CHAIRPERSON'S SPEECH AT CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP ON ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS

My esteemed colleagues from the National Human Rights Commission, Dr. P.L. Sanjeev Reddy, Director, IIPA, distinguished guests and participants in the workshop.

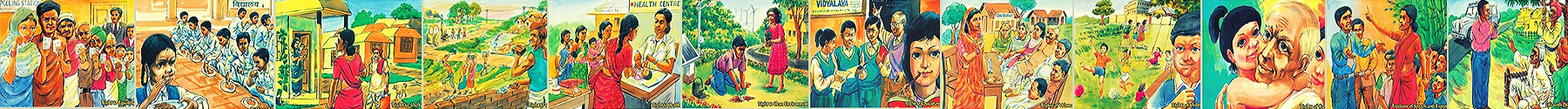

I welcome you all to this workshop and am extremely happy to be in your midst this morning at the inaugural session of the Workshop on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights being organized by the National Human Rights Commission, in collaboration with Indian Institute of Public Administration. The objective of this workshop is to sensitize the participants to the importance of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights - ICESCR and their application to domestic laws and public policy. The theme assumes significance, as millions of people in this country live in a state of abject poverty, without food, shelter, employment, health care and education. According to a UN Report, 1/5th of the population in a developing country, like ours, are hungry every night, 1/4th do not have access to basic amenities like drinking water and 1/3rd live in a state of acute poverty. Under ESCR, a State party is obliged to take steps to the maximum of its available resources with a view to achieving progressively, the full realization of the rights recognized in the Covenant by all appropriate means, including adoption of legislative measure which are to be exercised on a non-discriminatory basis. The obligations are essentially programmatic and promotional, to be fulfilled incrementally through the ongoing execution of a program.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which India is a State party, specifically recognizes the "fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger" and the right of everyone to "adequate food". It also recognizes the "right of everyone to education" and asserts that "primary education shall be compulsory and available free to all"; it further recognizes the "right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health". The Commission has construed these requirements to mean that the State has the obligation to ensure that these rights are respected and made available to the citizens.

The Founding Fathers of the Indian Constitution had a vision of the Indian society, which they wanted to realize through the Constitution. That vision was primarily reflected in the Preamble, the chapters on fundamental rights and directive principles. When WE THE PEOPLE OF INDIA Resolved to give to ourselves the Constitution, we aimed at securing for all its citizens - Justice, social, economic and political; Equality of status and opportunity besides Liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship and Fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation. The Indian Constitution, evolved after careful thought, is a dynamic living document, which carries the spirit of persuasion, of accommodation and of tolerance. It excludes the mention of certain basic economic and social rights, such as the right to food, right to shelter, right to work and right to medical care, from the chapter on fundamental rights contained in Part-III of the Constitution. Those rights have been made a part of directive principles of state policy in Part-IV of the Constitution.

Such distinction, however, has to be viewed from the historical context of the time when the Constitution was framed. Perhaps, in the backdrop of the then social-economic conditions of the Indian society, after about two hundred years of colonial subjugation, the framers of the Constitution evolved two sets of rights. In a way, the Fundamental Rights and the Directive Principles of State Policy are the product of human rights movement in the country. Roughly they represent, two streams in the evolution of human rights, which divide them between civil and political rights on the one hand and social, economic and cultural rights on the other. Justiciability is, essentially speaking, the basis of division between them. Whereas fundamental rights are justiciable, directive principles are not. Nonetheless, the Founding Fathers gave a mandate in Article 37, that the directive principles, though not enforceable by any court, are 'fundamental in the governance of the country and it shall be the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws'. Moreover, India, being a signatory to Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and other international instruments, is legally as well as morally committed to ensure basic human rights to all its citizens and enact laws accordingly. As a matter of fact, the development of human rights jurisprudence in the country is basically based on the Supreme Court expanding the concept of "right to life and liberty" under Article 21 so as to make the enjoyment of social, economic and cultural rights a reality. Both fundamental rights and directive principles of state policy are being increasingly construed by the courts harmoniously. This trend is reflected in the opinion of the Supreme Court in Minerwa Mills Ltd. Vs. Union of India where it was recognized that harmony between fundamental rights and directive principles of state policy was the basic feature of the Constitution.

Perhaps, realizing practical difficulties in the enforcement of directive principles by the courts, it appears that the founding fathers settled for their judicial non-enforceability but that does not mean that directive principles were in any way considered less important than fundamental rights. The resolve of the Preamble is elaborately repeated in the directive principles which, among others, specifically require, the State to minimize the inequalities in income and to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities. The directive principles require the state to take special care of education and economic interests particularly of the vulnerable sections of the society.

Thus, both civil and political rights on the one hand and economic, social and cultural rights on the other are indivisible and interdependent. While the former are more in the nature of injunctions against the State, the later are demands on the State to provide positive conditions to capacitate an individual to exercise the former. The object of both is to make the individual an effective participant in the affairs of the society for full development of human personality. In his remarkable study, "Development as Freedom", Professor Amartya Sen observed that the achievements of democracy depend not only on electoral politics and the rules of procedure that are adopted and safeguarded, but also on the ways in which the opportunities that democracy offers are used. In particular, Professor Sen wrote of the need to remove the major sources of three "unfreedoms" that afflict a society - Hunger, Illiteracy, Early Death - for democracy to have a true meaning and content.

The United Nations in 1986 recognised the right to development as a human right. The right to development as formulated in the 1986 U.N. declaration is a synthesis of two set of rights. However, the distinction between the two set of rights was put to rest by the 'Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action' which affirms that "All human rights are universal, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated". There is a direct co-relationship between human rights and development. Issues concerning food, nutrition, health care, shelter, employment and the like are intrinsically linked to ensure proper respect for human rights. There has to be a harmonious blending of all these rights to reach the objective, so as to provide human dignity.

For the Commission it has been important to link the issues of adequate food, education and health to that of human rights. It has been the view of the Commission that, when linked together, more can be done to advance human well-being than when food, education and health, on the one hand, and human rights, on the other, are considered in isolation. By setting these issues, additionally, in the context of combating the "unfreedoms" that thwart the promise of democracy, the Commissions has made fulfillment of these rights a further measure of the quality of governance both at the Centre and in the States.

With every passing year, conviction has grown in the Commission that for right to live with human dignity, it is essential to focus in equal measures on economic, social and cultural rights and civil and political rights. The indivisibility and interrelated nature of both these rights is a reality and there is a symbiosis between them. Those in the field must, therefore, ensure that the concern and anxiety which they show for political and social rights are also manifested in economic, social and cultural rights.

In his, perhaps the last speech before the Constituent Assembly, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar - the architect of India's Constitution - prophetically warned that India was

"going to enter into a life of contradiction. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man, one vote, one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to defy the principle of one man, one vote, and one value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradiction? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we shall do so by putting our political democracy at peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy which this Assembly has so laboriously built up."

We all need to act to remove the contradiction.

Let us, therefore, not delay the implementation of the covenants of the United Nations relating to economic, social and cultural rights. Let us rise to the occasion and ratify the treaties we have been delaying for so long so as, to give a practical shape to our resolve to protect and preserve human rights - let us give a new direction. Let us civilise and discipline public power for the betterment of the society. While seeking our rights, let us not over-look our duties and obligations as citizens. Let us assist the society to achieve equilibrium and not imbalance. Let us provide means for equality and not disparity; for development and not stagnation; for harmony and not discord; for solace and not misery; for abundance and not poverty; for love and not hatred and when we do so, we have hope and not despair.

This workshop will, I hope, help in identifying issues, programmes and policies that are human rights friendly and re-orient attitudes and priorities across the entire range and spectrum of governmental endeavour.

The senior officers participating in the Workshop will, I hope, carry a firm message back home, to see that these rights are widely disseminated down the line.

It now gives me great pleasure to inaugurate this Workshop and wish you all the best of luck.

Thank you.

******

I welcome you all to this workshop and am extremely happy to be in your midst this morning at the inaugural session of the Workshop on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights being organized by the National Human Rights Commission, in collaboration with Indian Institute of Public Administration. The objective of this workshop is to sensitize the participants to the importance of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights - ICESCR and their application to domestic laws and public policy. The theme assumes significance, as millions of people in this country live in a state of abject poverty, without food, shelter, employment, health care and education. According to a UN Report, 1/5th of the population in a developing country, like ours, are hungry every night, 1/4th do not have access to basic amenities like drinking water and 1/3rd live in a state of acute poverty. Under ESCR, a State party is obliged to take steps to the maximum of its available resources with a view to achieving progressively, the full realization of the rights recognized in the Covenant by all appropriate means, including adoption of legislative measure which are to be exercised on a non-discriminatory basis. The obligations are essentially programmatic and promotional, to be fulfilled incrementally through the ongoing execution of a program.

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, to which India is a State party, specifically recognizes the "fundamental right of everyone to be free from hunger" and the right of everyone to "adequate food". It also recognizes the "right of everyone to education" and asserts that "primary education shall be compulsory and available free to all"; it further recognizes the "right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health". The Commission has construed these requirements to mean that the State has the obligation to ensure that these rights are respected and made available to the citizens.

The Founding Fathers of the Indian Constitution had a vision of the Indian society, which they wanted to realize through the Constitution. That vision was primarily reflected in the Preamble, the chapters on fundamental rights and directive principles. When WE THE PEOPLE OF INDIA Resolved to give to ourselves the Constitution, we aimed at securing for all its citizens - Justice, social, economic and political; Equality of status and opportunity besides Liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith and worship and Fraternity assuring the dignity of the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation. The Indian Constitution, evolved after careful thought, is a dynamic living document, which carries the spirit of persuasion, of accommodation and of tolerance. It excludes the mention of certain basic economic and social rights, such as the right to food, right to shelter, right to work and right to medical care, from the chapter on fundamental rights contained in Part-III of the Constitution. Those rights have been made a part of directive principles of state policy in Part-IV of the Constitution.

Such distinction, however, has to be viewed from the historical context of the time when the Constitution was framed. Perhaps, in the backdrop of the then social-economic conditions of the Indian society, after about two hundred years of colonial subjugation, the framers of the Constitution evolved two sets of rights. In a way, the Fundamental Rights and the Directive Principles of State Policy are the product of human rights movement in the country. Roughly they represent, two streams in the evolution of human rights, which divide them between civil and political rights on the one hand and social, economic and cultural rights on the other. Justiciability is, essentially speaking, the basis of division between them. Whereas fundamental rights are justiciable, directive principles are not. Nonetheless, the Founding Fathers gave a mandate in Article 37, that the directive principles, though not enforceable by any court, are 'fundamental in the governance of the country and it shall be the duty of the State to apply these principles in making laws'. Moreover, India, being a signatory to Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and other international instruments, is legally as well as morally committed to ensure basic human rights to all its citizens and enact laws accordingly. As a matter of fact, the development of human rights jurisprudence in the country is basically based on the Supreme Court expanding the concept of "right to life and liberty" under Article 21 so as to make the enjoyment of social, economic and cultural rights a reality. Both fundamental rights and directive principles of state policy are being increasingly construed by the courts harmoniously. This trend is reflected in the opinion of the Supreme Court in Minerwa Mills Ltd. Vs. Union of India where it was recognized that harmony between fundamental rights and directive principles of state policy was the basic feature of the Constitution.

Perhaps, realizing practical difficulties in the enforcement of directive principles by the courts, it appears that the founding fathers settled for their judicial non-enforceability but that does not mean that directive principles were in any way considered less important than fundamental rights. The resolve of the Preamble is elaborately repeated in the directive principles which, among others, specifically require, the State to minimize the inequalities in income and to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities. The directive principles require the state to take special care of education and economic interests particularly of the vulnerable sections of the society.

Thus, both civil and political rights on the one hand and economic, social and cultural rights on the other are indivisible and interdependent. While the former are more in the nature of injunctions against the State, the later are demands on the State to provide positive conditions to capacitate an individual to exercise the former. The object of both is to make the individual an effective participant in the affairs of the society for full development of human personality. In his remarkable study, "Development as Freedom", Professor Amartya Sen observed that the achievements of democracy depend not only on electoral politics and the rules of procedure that are adopted and safeguarded, but also on the ways in which the opportunities that democracy offers are used. In particular, Professor Sen wrote of the need to remove the major sources of three "unfreedoms" that afflict a society - Hunger, Illiteracy, Early Death - for democracy to have a true meaning and content.

The United Nations in 1986 recognised the right to development as a human right. The right to development as formulated in the 1986 U.N. declaration is a synthesis of two set of rights. However, the distinction between the two set of rights was put to rest by the 'Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action' which affirms that "All human rights are universal, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated". There is a direct co-relationship between human rights and development. Issues concerning food, nutrition, health care, shelter, employment and the like are intrinsically linked to ensure proper respect for human rights. There has to be a harmonious blending of all these rights to reach the objective, so as to provide human dignity.

For the Commission it has been important to link the issues of adequate food, education and health to that of human rights. It has been the view of the Commission that, when linked together, more can be done to advance human well-being than when food, education and health, on the one hand, and human rights, on the other, are considered in isolation. By setting these issues, additionally, in the context of combating the "unfreedoms" that thwart the promise of democracy, the Commissions has made fulfillment of these rights a further measure of the quality of governance both at the Centre and in the States.

With every passing year, conviction has grown in the Commission that for right to live with human dignity, it is essential to focus in equal measures on economic, social and cultural rights and civil and political rights. The indivisibility and interrelated nature of both these rights is a reality and there is a symbiosis between them. Those in the field must, therefore, ensure that the concern and anxiety which they show for political and social rights are also manifested in economic, social and cultural rights.

In his, perhaps the last speech before the Constituent Assembly, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar - the architect of India's Constitution - prophetically warned that India was

"going to enter into a life of contradiction. In politics we will be recognizing the principle of one man, one vote, one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to defy the principle of one man, one vote, and one value. How long shall we continue to live this life of contradiction? How long shall we continue to deny equality in our social and economic life? If we continue to deny it for long, we shall do so by putting our political democracy at peril. We must remove this contradiction at the earliest possible moment or else those who suffer inequality will blow up the structure of political democracy which this Assembly has so laboriously built up."

We all need to act to remove the contradiction.

Let us, therefore, not delay the implementation of the covenants of the United Nations relating to economic, social and cultural rights. Let us rise to the occasion and ratify the treaties we have been delaying for so long so as, to give a practical shape to our resolve to protect and preserve human rights - let us give a new direction. Let us civilise and discipline public power for the betterment of the society. While seeking our rights, let us not over-look our duties and obligations as citizens. Let us assist the society to achieve equilibrium and not imbalance. Let us provide means for equality and not disparity; for development and not stagnation; for harmony and not discord; for solace and not misery; for abundance and not poverty; for love and not hatred and when we do so, we have hope and not despair.

This workshop will, I hope, help in identifying issues, programmes and policies that are human rights friendly and re-orient attitudes and priorities across the entire range and spectrum of governmental endeavour.

The senior officers participating in the Workshop will, I hope, carry a firm message back home, to see that these rights are widely disseminated down the line.

It now gives me great pleasure to inaugurate this Workshop and wish you all the best of luck.

Thank you.

******